Historical and Cultural Reconnection: Dhaka, Bangladesh

This November I travelled overseas for the first time since the COVID-19 pandemic began. Although not a common tourist destination, Bangladesh is the country where I was born and this trip gave me the opportunity to explore the history and culture of my country through fresh eyes. Connecting to my roots and learning about how my family's history is intertwined with the history of the nation was an enriching experience.

Dhaka has been occupied for centuries, with initial settlement dating from the first millennium. The city became the capital of Bengal in the early 17th century under the rule of the Mughals, the Muslim dynasty that ruled this area from the 16th to 18th century. In the early 20th century Dhaka was designated the capital of Eastern Bengal and Assam under British rule. In this post I run through some of the highlights of my time in Dhaka, the nation's capital where my family is based.

Bangladesh National Museum

The Bangladesh National Museum is located next to the University of Dhaka, the oldest university in Bangladesh. Both were established around the same time, the museum initially as Dacca Museum in 1913, and the university in 1921. The museum displays historical, cultural and natural artefacts and objects from around Bangladesh and the eastern Bengal region over three floors of galleries.

A large part of the museum's gallery space is dedicated to displays about the formation of Bangladesh as an independent nation. During the partition of India in 1947 when British rule ended, the region of Bengal was split in two, with West Bengal located within the borders of India and East Bengal, in the current borders of Bangladesh, designated as East Pakistan and administered by Pakistan to India's west.

International Mother Language Institute

Located in my grandparents' neighbourhood on the other side of Ramna Park, a lush city park I played in as a toddler, is the International Mother Language Institute. The institute serves to commemorate and educate on the history of the Bangla language and native languages around the world more broadly, promoting linguistic diversity and preservation. The outer facade of the building displays symbols from many different scripts, a visual representation of the aim of the institute.

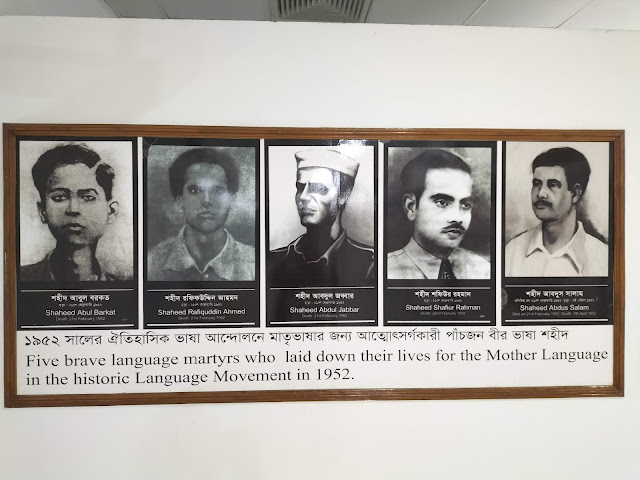

The institute has a Language Museum on the ground floor, a gallery of scripts including current and extinct languages on the sixth floor, and a library on the fifth floor. Just inside the entrance is a sign commemorating five of the Bengali people who died for the Bangla Language Movement in 1952. This movement was a response to the enforcement of the Urdu language as the only national language of Pakistan, then comprising West and East Pakistan. On 21st February 1952, University of Dhaka students organised a protest despite the Pakistani government banning public gatherings, and the police killed student protestors, including those seen below.

|

| Shaheed Minar (Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 3.0) |

Based on a proposal submitted by a group of Bangladeshis to the Secretary General of the United Nations in 1999, UNESCO declared the 21st of February as International Mother Language Day, a day to promote linguistic and cultural diversity and multilingualism.

Alongside the story of the Bangla Language Movement and Bangladeshi Independence, and the history of International Mother Language Day, the Institute's museum includes profiles on languages spoken in countries across the world. The Australian profile shown below was particularly interesting to me, and includes many Indigenous Australian languages.

Old Dhaka

Old Dhaka (Puran Dhaka in Bangla) is in the southern part of Dhaka's current extent, referring to the historic part of the city founded in the early 17th century by the Mughal dynasty as the capital of Bengal. Puran Dhaka is a wonderful mix of traders and markets selling food, spices, garments and many other wares, and incredibly diverse architecture is dotted throughout the narrow winding streets, including mosques, temples, and even an Armenian church from the 18th century.

One point of interest in Puran Dhaka is the Ahsan Manzil Museum, a historical museum housed within a structure on the northern bank of the Buriganga River. The building was originally the house of the Nawabs of Dhaka, aristocratic land-owning families recognised by the Mughals and later the British Empire. The most striking feature of the building is its exterior, painted in a bright pink colour for the opening of the museum in 1992. The museum traces the two levels of the building and remnants of its grand architecture and furnishings can be viewed from inside.

Further west is Lalbagh Fort, constructed in the late 17th century as the residence of the Mughal governor of Bengal. The fort is situated in a large garden compound, with structures including the two-storey residence with distinctive reddish Mughal facade, a tomb and a mosque. The wide gardens provide many places for visitors to sit for some respite from the busyness of the streets of Old Dhaka beyond the fort's walls.

Sonargaon

About an hour southeast of Dhaka is Sonargaon, a historic city in Bengal used for administration under subsequent periods of the Delhi sultanate, Bengal sultanate, Mughal and British rule, and prior to that thought to house an older ancient Hindu settlement. One of the main points of interest in the city is the Bangladesh Folk Arts & Crafts Foundation which includes a museum attesting the handicrafts of the Bengal region. Nearby is Panam City, a historic street visitors can walk down with striking buildings in various states of preservation on either side, blending components of South Asian and British architectural styles, such as the building below.

Comments

Post a Comment